In January 2021 I wrote a blogpost called ‘The Snapback’. We had just come out of a year where the higher education sector was profoundly disrupted by the pandemic. Every aspect of how we conducted teaching, learning and assessment was jumbled and rebuilt through the harsh prism of lockdowns, border closures, fear, and the increasing risks of getting seriously ill from a virus we didn’t understand. In the main, the response by educational technologists, learning designers, developers and committed academics was nothing short of magnificent. The pivot to remote teaching was more than a reflex response enabled by technology-led mode shifting. The knowledge, expertise and capacity to learn through experience saw the deployment of inventive, novel, creative and effective approaches to the rapid upskilling of staff and students, the design of online learning and the building of communities of engaged learners spread across the world. I know this to be true because it happened right in front at me, at my Business School through the intense dedication and determination of the Business Co-Design team, who worked collaboratively with a group of academics wanting more for their students than multiple choice questions and last year’s lecture recordings.

In the midst of that storm, that blog post warned of an impending crisis, and that was the very real threat of what I called the Snapback. My prediction was that once the pandemic ‘ended’ (or was deemed to have ended by government) universities would snap back to the teaching practices of 2019 (large lectures, pen and paper exams, for example). I argued that the snap back was a reaction to the trauma and intensity of the collective liminality we all experienced during the pandemic. Any reminder of that experience, whether it be the sight of a mask or the opening of another zoom room could trigger an institutional or personal post-traumatic reaction. that reminds us of how uncertain journeying away from the established social behaviours of teaching. Now the emergency has ‘ended’ and we can snap back to how we used to teach. We can imagine a world where COVID never happened. That kind of protective self-deception allows us to inhabit a 2019 nirvana university. No remote, no hybrid and full lectures brimming with people who want to listen to US.

Finding that nirvana however requires us to unlearn everything that we experienced during the pandemic. A culture of unlearning marginalises those who don’t think 2019 was peak education because their exhortations to learn from the pandemic also remind us of ‘the bad times’. The easiest way to unlearn and begin your journey back to 2019 is to disrupt the value proposition that there was anything to learn from remote teaching in the first place. We only did it because the pandemic forced us to. Disrupting the value proposition involves demeaning remote learning as a poor substitute, which could never be as good as the face-to-face experience or vilifying those who advocate for learning from the experience as not understanding teaching or even worse being irrationally scared of COVID (does ‘we have to learn to live with COVID’ sound familiar in this context?).

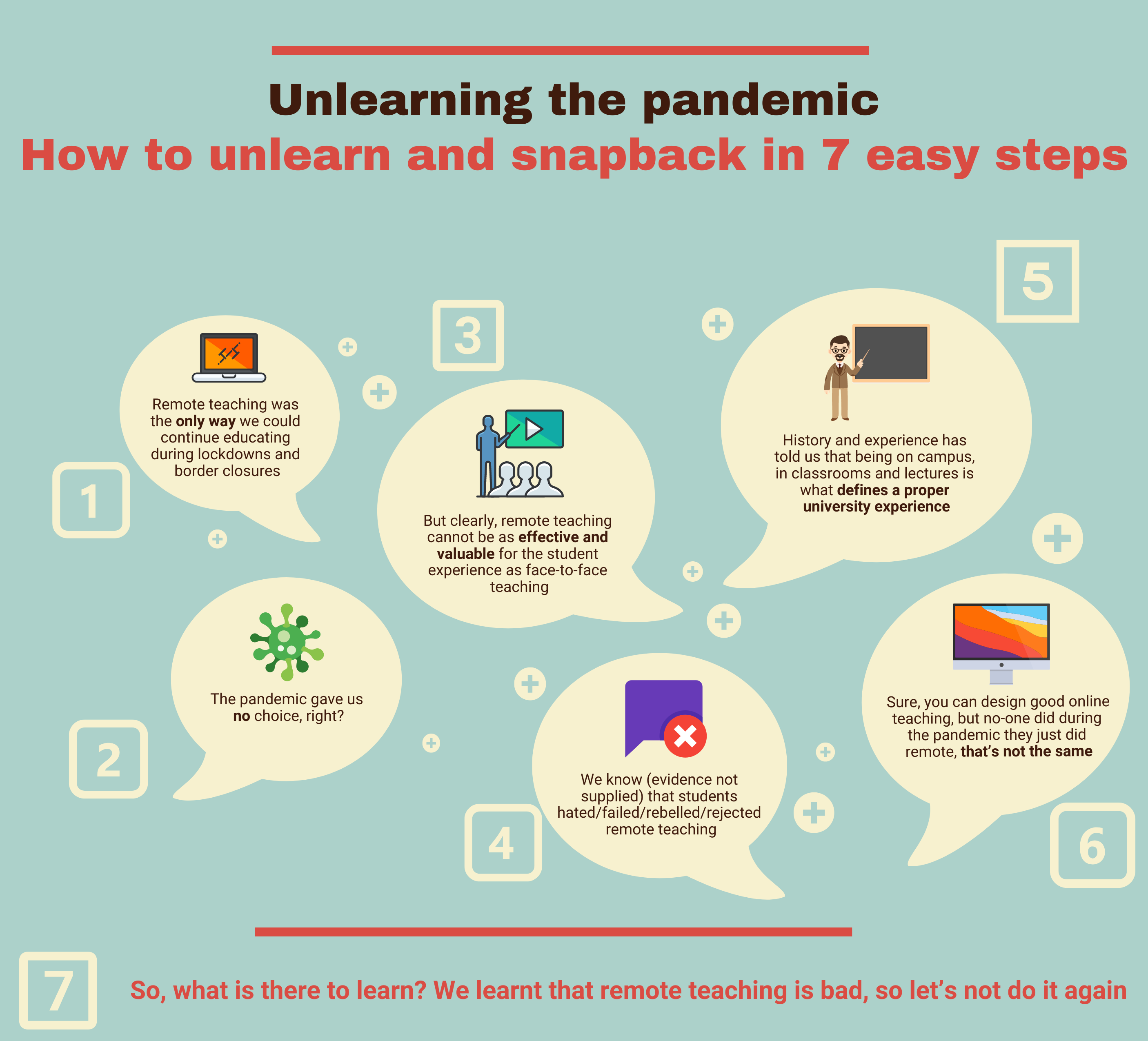

There are seven easy steps you can take to disrupt the value proposition that remote teaching has any value, and you too can go back to 2019 and enjoy the winner of the Eurovision Song Contest held in Tel Aviv. Ladies and Gentlemen I give you Duncan Lawrence from the Netherlands.

Unlearning the pandemic in 7 easy steps

1. Remote learning was the only way we could continue teaching during lockdowns and border closures.

2. The pandemic gave us no choice, right?

3. But clearly, remote teaching cannot be as effective and valuable for the student experience as face-to-face teaching

4. We know (evidence not supplied) that students hated/failed/rebelled/rejected remote teaching

5. History has told us that being on campus, in classrooms and lectures is what defines a proper university experience

6. Sure, you can design good online teaching, but no-one did during the pandemic they just did remote, that’s not the same

7. So, what is there to learn? We learnt that remote teaching is bad, so let’s not do it again

Learning forward, not snapping back

Snapping back seems easy, comfortable and from the perspective of those want to snap back to the old ways of teaching, absolutely the right thing to do, because remote teaching led to bad outcomes, stressed staff, isolated students, and broken campuses. The reality is that remote teaching didn’t do that, the pandemic did. Remote teaching was not BAD. There were immediate and long-term benefits that came from how we engaged collectively in remote and then hybrid teaching. We graduated students, we helped them navigate a period of uncertainty, fear, and isolation. We kept the social and economic good of the institution going.

1/2 As it seems the entire HE sector is snapping back to peak education (2019 stylz) let’s remember that remote learning was not ALL BAD. We learnt how to be more accessible, more diverse, more experimental & innovative, more open to how connection collaboration can be enabled.

— Peter Bryant (@PeterBryantHE) October 28, 2022

2/2 We became less didactic & we delivered +ve outcomes for students. Remote isn’t the antithesis of good education. Unless we remember the learning like we ask our students to, then all we will do is go around in the same circles that might be comfortable but not inspiring.

— Peter Bryant (@PeterBryantHE) October 28, 2022

The challenge for institutions, but also for academics, developers, designers and all of us involved in the innovation of education is how to understand, evidence and argue for those benefits in the context of what teaching and learning should become. This is not the old technology will save us debate. And it’s not a call to keep teaching remotely. This is an opportunity to design learning for the post-pandemic future. A new way to undertake teaching and learning that is adaptive and responsive to the lives and priorities of our students, co-designing their experiences in ways that redefine the role of the university in their lives, and the roles they will play shaping society, their communities and themselves.

To achieve this, we need to learn forward and not snap back. Learning forward means listening to and understanding the experiences that students, staff, employers and the wider community had during the pandemic so that we can co-design a better education. We can recontextualise the experiences of hybrid learning, online assessment, asynchronous engagement, and flexibility to design and a deliver a more accessible, more diverse, more experimental and innovative model of higher learning. A model that addresses some of the critical inequities exposed by the pandemic around literacy gaps, digital and data poverty, transitions, and access to higher education (amongst many others). Learning forward uses the skills many of us hope to instil in our students. The capabilities required to learn from experience, and then apply that learning to often radically different circumstances in an unknown and uncertain future. The flexibility to adapt to different modes of teaching, enabling both the advantages and opportunities that technology, face-to-face and hybrid contexts can offer.

In my own place, we got things like connection, collaboration, and reflexivity right during the pandemic. There was nothing lonelier than your classroom becoming the same room you watched TV in, played games in, listened to music in and then had breakfast, lunch, and dinner in. The windows into the worlds of your colleagues, your friends, your cohort were 5cm by 5cm, blurred or even blank. We learned how to make engagement and collaboration safe, valued and central to the learning experience, in part because we had spent years understanding connected learning at scale, but equally in the dumpster fire of 2020 we knew we had to build a sense of belonging, a feeling of community and a deep sense of association and empathy. We didn’t do it in every unit and we didn’t always get it right, but we did it in some and where it worked, it really worked. We expanded our co-curricular engagement, running large-scale ambitious programs on leadership for good and managing the impacts of crisis. Learning forward for us is about understanding how, in a post-pandemic world entering a period of deep and prolonged economic uncertainty, we can redesign educational opportunities that realise the possibilities we glimpsed during the pandemic and deeply integrate them into the learning and teaching experience.

None of this rocket science. Learning from experience makes good pedagogical sense. The problem is that the snapback is stronger and more damaging than I predicted in 2021. Governments have demonised online learning, threatening penalties and payback to those who persist in it. Engaging in online delivery is labelled as being non-compliant by regulators. Institutions publicly state on the websites that remote learning whilst necessary was never as effective as face-to-face, so let’s celebrate the return. The snap back has been accelerated by the impacts of predatory behaviour of vendors profiteering off the traumatised higher education sector and in part by rogue traders in online learning hawking the ideas, practices, and pedagogies they had been keeping in the bottom drawer of their desk for years. But the biggest factor that is holding us back from learning from the pandemic to emerge a stronger, better educator is ourselves. Snapping back feels safe after three years of being afraid. Snapping back means we can stop thinking about how we teach, and we can just be there and turn up. Snapping back is comfortable and risk-free, instead of worrying what will happen when zoom crashes or the internet goes down during the exam.

Students deserve to have the full face to face teaching experience they would have received before the pandemic – online learning should only be used to supplement this. This week I am personally calling VCs who aren’t delivering this. https://t.co/TuKTexiXaF

— Michelle Donelan MP (@michelledonelan) January 17, 2022

Online learning at university should complement in-person teaching, not detract from it ????????

Students should rightly expect face-to-face teaching and can raise concerns if the expected standards are not being met.

My open letter to students??????https://t.co/lvGhcnz6wT

— Nadhim Zahawi (@nadhimzahawi) January 17, 2022

The pandemic moved the sector into a liminal state, dissolving our identity as educators and disorienting us from the practices that we were comfortable. Liminality is a journey away from social structures and systems through uncertainty to a different social state. Victor Turner argues that most liminal states eventually dissolve because the intensity of the experience cannot be sustained without the liminal individuals seeking to return to the safety of the original social structures or coalescing together with others to form a new perduring social structure (what he calls a normative communitas). The snapback and the heady days of 2019 are the return to safety for academics, the re-imagination of a new future for education remains uncertain, liminal and will, as always pedagogical change does, require a rite of passage. In the 2021 post, I posed the following question (written during a lockdown and before both Delta and Omicron became dominant):

What I am interested in debating is what happens when you cease to be liminal; when you return to your stable social state (or discover or design a new one), where the norms of practice come snapping back. What happens when the pandemic (crisis, black swan moment, opportunity) ends and staff and students want to stop feeling liminal and transition back to certainty?

This is our opportunity to coalesce into what Victor Turner calls a normative communitas and stop feeling liminal without snapping back to practices that were not working in 2019. Lecture theatres were empty, student satisfaction was in decline in many institutions and government policy was regulating all the social good out of university, replacing it with instrumentalist approaches to employability. People who want to learn forward, share their critical reflections and experiences, and help others on the journey are not alone. We are more than a conference presentation, an academic paper, a blog post, or a tweet. We are a community of shared knowledge, we exist in spaces and places not entirely represented by associations, SIGS or institutions. We don’t have to return to our surrounding social structures. We can learn from remote teaching, learn from ours and others experience and we can collectively redesign education for the unknown and uncertain post-pandemic future.

BUT, and this is a BIG BUT, just saying it, or wishing it or tweeting about it will not be enough. We need to evidence our learning, with our voices and those of the students. We need to engage in storytelling and story making that others want to hear and share. We need to design social structures and systems that are informed by what we learnt from the experience of higher education during the pandemic. The evidence we use needs to be persuasive. Our messages need to cut through and the actions we take need to be co-designed with students who experienced liminality during the pandemic in vastly different ways (and many continue to do so today). We need to imagine what the next iteration of learning, teaching and assessment looks like and then be leaders for vision, ambition, and possibilities it represents. As much as I liked the song Arcade in 2019, I can’t wait to discover what the 2023 Eurovision Song Contest in Liverpool will bring to the party.

(thanks to the Underground Lovers for the blog title, from the track I Was Right, from 1992s LP Leaves Me Blind)

Header picture by Ante Hamersmit on Unsplash

One thought on “‘…and the way that it ends is that the way it began’: Why we need to learn forward, not snap back”